Netflix criticized for yanking comedian's episode in Saudi

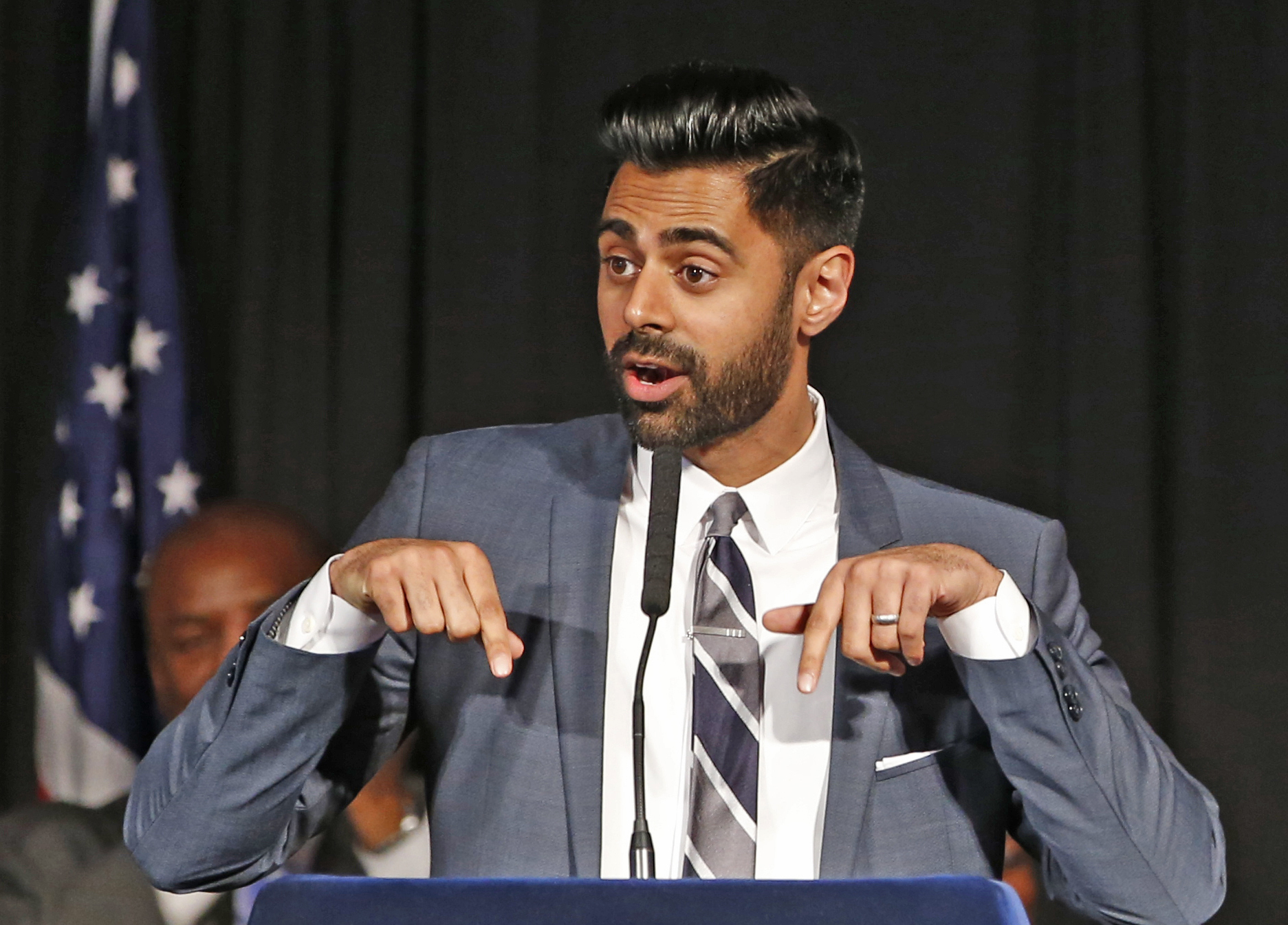

NEW YORK (AP) — Netflix faced criticism Wednesday from human rights groups for pulling an episode in Saudi Arabia of comedian Hasan Minhaj’s “Patriot Act” series that criticized the kingdom’s powerful crown prince.

The American comedian used his second episode, released Oct. 28, to criticize Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman over the killing of writer Jamal Khashoggi and the Saudi-led coalition at war in Yemen.

Human rights group Amnesty International said Saudi Arabia’s censorship of Netflix is “further proof of a relentless crackdown on freedom of expression.” PEN America, the literary and human rights organization, said the move “legitimizes repression.” Netflix said it was simply complying with a local law.

Khashoggi, who wrote critically of the crown prince in columns for the newspaper, was killed and dismembered by Saudi agents inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul last year. The U.S. Senate has said it believes the crown prince is responsible for the grisly killing, despite insistence by the kingdom that he had no knowledge of the operation.

“It blows my mind that it took the killing of a Washington Post journalist for everyone to go: ‘Oh I guess he’s not really a reformer,'” Minhaj said in the episode.

Netflix, in a statement Wednesday, said the episode was removed from the kingdom as a result of a legal request from authorities and not due to its content.

“We strongly support artistic freedom worldwide and removed this episode only in Saudi Arabia after we had received a valid legal demand from the government — and to comply with local law,” the streaming giant said.

Minhaj, a former correspondent with “The Daily Show” on Comedy Central, told The Associated Press this summer that his Netflix show would fuse his personal narrative as a first-generation Indian-American with the current political and social backdrop to examine deep issues confronting the world.

In the roughly 18-minute now-censored “Patriot Act” monologue, Minhaj also mentions the ruling Al Saud family and its vast wealth, saying: “Saudi Arabia is crazy. One giant family controls everything.”

In a tweet, Minhaj mocked the censorship attempt, pointing out that the episode banned from the kingdom is available elsewhere online.

“Clearly, the best way to stop people from watching something is to ban it, make it trend online, and then leave it up on YouTube,” he tweeted.

The Saudi-led coalition’s airstrikes in Yemen have also come under intense scrutiny since Khashoggi’s killing. The war, which began in March 2015, has killed thousands of civilians and pushed millions to the brink of famine.

The Financial Times first reported that Netflix yanked the episode. The episode had been available in Saudi Arabia since late October but was pulled in December after the legal request. Only the second episode has been pulled and it is available to subscribers elsewhere.

The kingdom’s Communication and Information Technology Commission said the episode was in violation of Article 6, Paragraph 1 of the Anti-Cyber Crime Law in Saudi Arabia. Officials at the commission could not be immediately reached for comment.

But Samah Hadid at Amnesty International said “Netflix is in danger of facilitating the kingdom’s zero-tolerance policy on freedom of expression and assisting the authorities in denying people’s right to freely access information.”

And Summer Lopez, PEN America’s senior director of Free Expression Programs, said the request by the kingdom was “part of Saudi Arabia’s standard playbook of repression.”

“While Netflix may see no option but to comply, they should be transparent about those decisions and accompany any such action with a clear statement opposing the imposition of censorship,” Lopez said. “Powerful global corporations are in a unique and important position to push back against requests to censor speech, and failing to do so legitimizes repression.”

The Saudi cyber-crime law states that “production, preparation, transmission, or storage of material impinging on public order, religious values, public morals, and privacy, through the information network or computers” is a crime punishable by up to five years in prison and a fine, according to rights group Amnesty International.

Saudi prosecutors have used the broadly worded law to imprison rights activists, poets and others who have expressed views deemed critical of the government or its policies on social media.

Since Prince Mohammed was named heir to the throne in mid-2017, dozens of writers, activists and moderate clerics have been jailed.

Among those detained since May of last year are women’s rights activists who had long pushed for more freedoms, including the right to drive before it became legal in June.

Several people with knowledge of their arrest have told The Associated Press that some of the women detained have been subjected to caning, electrocution, and others were also sexually assaulted.

Netflix’s streaming service expanded into Saudi Arabia three years ago. The company doesn’t give subscriber numbers for any country besides the U.S. but the number of customers it has in Saudi Arabia accounts for an extremely small fraction of its 137 million worldwide subscribers.

___

Mark Kennedy is at http://twitter.com/KennedyTwits

The Western Journal has not reviewed this Associated Press story prior to publication. Therefore, it may contain editorial bias or may in some other way not meet our normal editorial standards. It is provided to our readers as a service from The Western Journal.

Truth and Accuracy

We are committed to truth and accuracy in all of our journalism. Read our editorial standards.

Advertise with The Western Journal and reach millions of highly engaged readers, while supporting our work. Advertise Today.