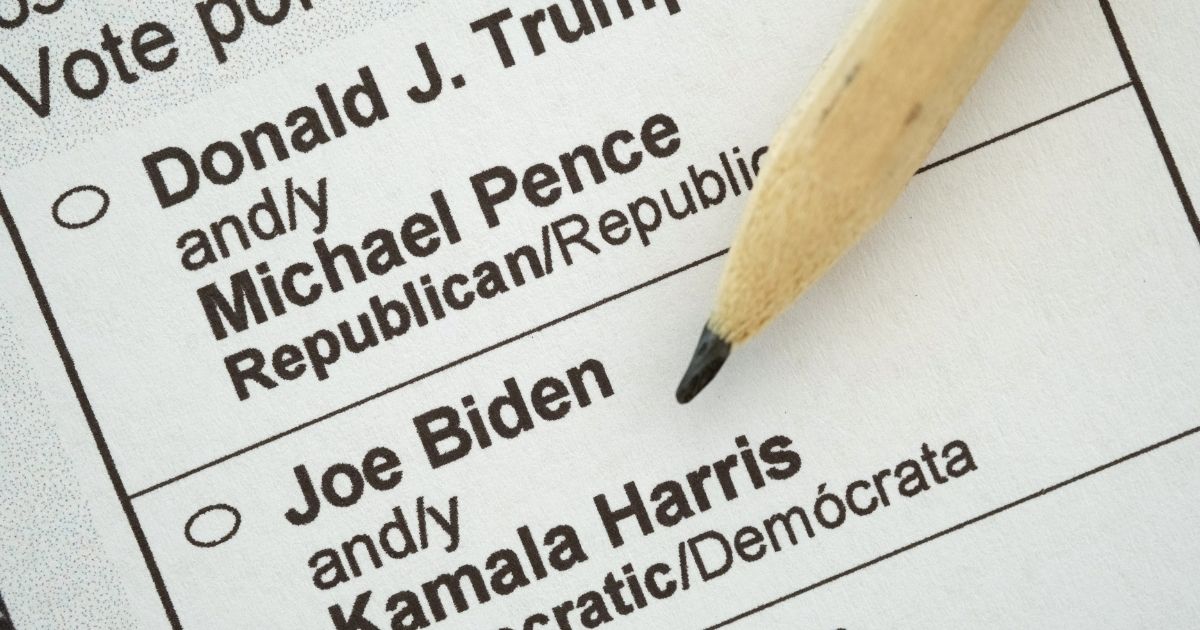

Mail-In Ballots Set Stage for Next 'Hanging Chad' Debacle

Two decades ago, Florida’s hanging chads became an unlikely symbol of a disputed presidential election. This year, the issue could be poorly marked ovals or boxes.

Amid the coronavirus pandemic, Democrats are pushing voters to bypass their polling places and cast absentee ballots for the first time.

Voters marking ballots from home could lead to an increase in the kinds of mistakes that typically would be caught by a scanner or election worker at the polls. Experts say that’s likely to mean more ballots with questionable marks requiring review.

President Donald Trump has repeatedly questioned the integrity of mail-in voting, and his campaign has already challenged aspects of it in court.

While ballots subject to review have historically represented a tiny portion of overall ballots, it’s possible disputes could arise and end up as part of a Florida-like fight, especially in battleground states like Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania.

“This could be 2000’s hanging chad in Pennsylvania,” according to Suzanne Almeida, interim director of the state chapter of the nonpartisan watchdog Common Cause.

“Potential challenges, delays in results, questions on which ballots count and who counts them — there are just a lot of questions, and that could open up Pennsylvania to a lot of uncertainty.”

The group is working with election officials statewide, emphasizing clear and consistent guidelines for dealing with questionable marks, such as when a voter circles a name or uses an X or a checkmark rather than filling in the oval.

While all states perform ballot reviews and have rules related to voter intent, some have never seen anything like this year’s anticipated absentee ballot volume.

In half the states, absentee ballots accounted for less than 10 percent of votes cast in 2016. Many could see half or more votes cast absentee this fall.

Amber McReynolds, who formerly ran Denver’s elections office, said consistency and detailed guidelines are essential. Otherwise, counties might perform reviews differently, leading to further challenges.

“You don’t want to have a situation where you have one type of mark in a county that is processed and counted and in another it isn’t,” McReynolds, who now leads the National Vote at Home Institute, said.

Safeguards built into the nation’s myriad election systems to help voters avoid ballot-marking problems are mostly geared toward in-person voting.

Touchscreen voting machines — though considered less secure — do a better job than humans in marking ballots and warning voters if they try to vote twice in the same race.

“But now, if most people are not voting with machines and are voting at home, they are not going to have that notification,” Larry Norden, an elections expert with the Brennan Center for Justice, said.

Experts point to Georgia’s experience after the June primary as a cautionary tale.

During vote counting, some counties reported what appeared to be valid votes that weren’t flagged for review by the state’s new high-capacity ballot scanners, which process large volumes of absentee ballots at once.

It turned out the scanner software was set to flag ballots with between 12 percent and 35 percent of an oval shaded. Anything more was automatically counted. Anything less was not.

Setting such parameters for ambiguous marks is a common practice.

Jeanne Dufort, who served as the Democrat on the review panel in Morgan County, east of metro Atlanta, said that in previous years absentee ballots represented a small fraction of votes cast and those reviewed had usually been damaged in some way.

But this time, the software flagged about 150 ballots out of roughly 3,000 cast. In one case, a voter had marked ovals using a smiley face. The panel also discovered roughly 20 votes that had gone unrecorded and were not flagged for review, Dufort said.

She noted the stakes will be higher in November.

“A vote review panel’s purpose is to make up for the limits of technology,” Dufort said. “It’s a pretty solemn responsibility.”

Georgia has since revised its software. Training videos were also distributed.

Experts also note other concerns heading into November, primarily that ballots could be rejected for issues such as a missing signature or one that doesn’t match the one on file.

In Pennsylvania, there are worries ballots could be rejected because voters don’t put them inside a “secrecy envelope” and then into a second, mailing envelope.

“All this doesn’t matter much, until it does,” Mark Lindeman, co-director of Verified Voting, said.

“It’s unusual for an election to hinge on ambiguously marked ballots, but it can happen.”

The Western Journal has reviewed this Associated Press story and may have altered it prior to publication to ensure that it meets our editorial standards.

Truth and Accuracy

We are committed to truth and accuracy in all of our journalism. Read our editorial standards.

Advertise with The Western Journal and reach millions of highly engaged readers, while supporting our work. Advertise Today.