Divers May Have Found Sunken US Submarine at Center of Harrowing WWII Saga

Divers have found what they believe is the wreck of a U.S. Navy submarine lost 77 years ago in Southeast Asia, providing a coda to a stirring but little-known tale from World War II.

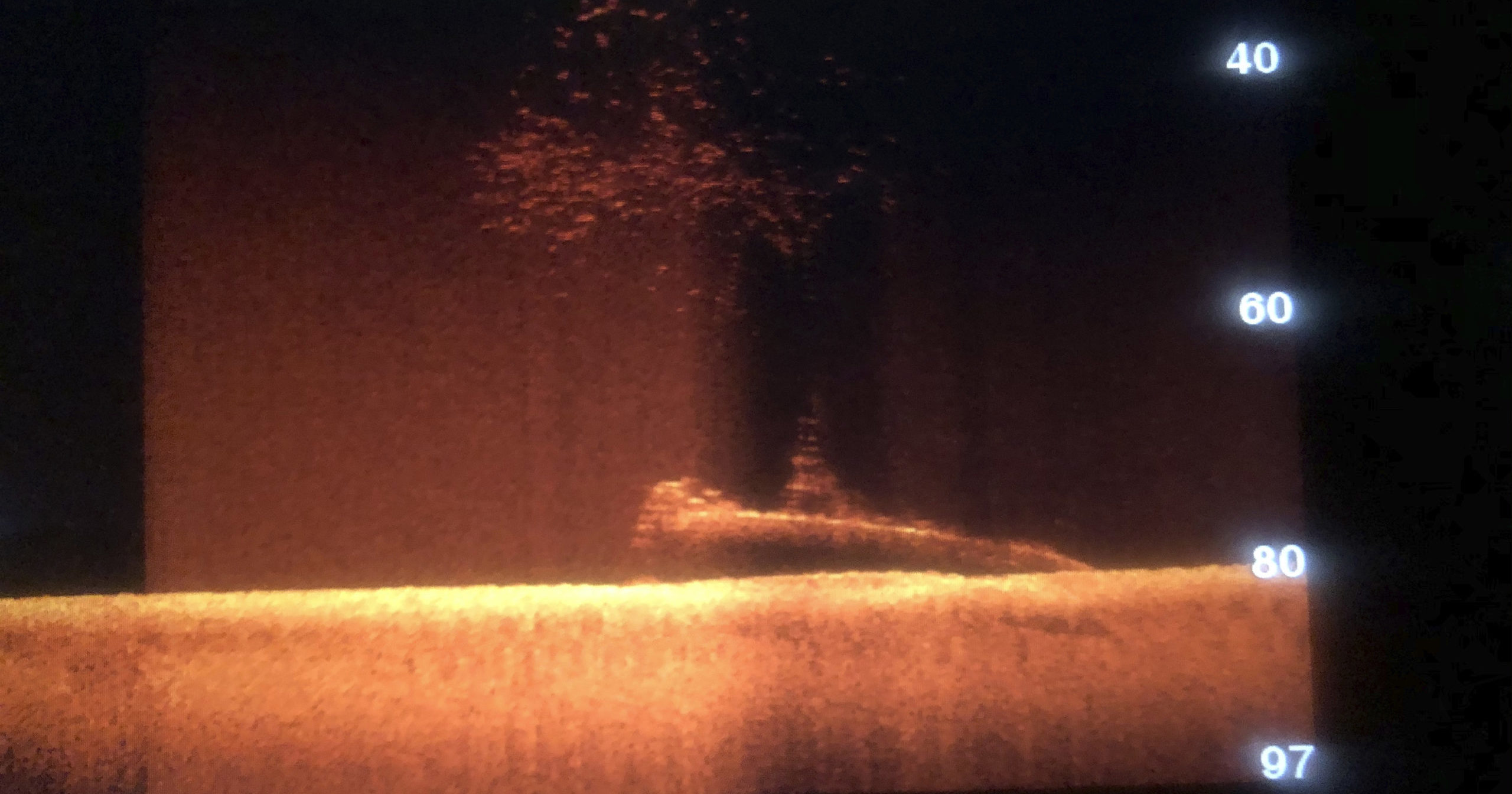

The divers have sent photos and other evidence from six dives they made from October 2019 to March this year to the United States Naval History and Heritage Command for verification that they have found the USS Grenadier, one of 52 American submarines lost during the war.

The 1,475-ton, 307-foot long Grenadier was abandoned by its crew after bombs from a Japanese plane almost sent them to a watery grave. All 76 of its personnel survived the bombing and sinking, but their trials did not end there.

After being taken prisoner, they were tortured, beaten and nearly starved by their Japanese captors for more than two years, and four did not survive the ordeal.

The wreck lies 270 feet underwater in the Strait of Malacca, about 92 miles south of Phuket, Thailand.

It was discovered by Singapore-based Jean Luc Rivoire and Benoit Laborie of France and Australian Lance Horowitz and Belgian Ben Reymenants, who live in Phuket, Thailand.

Reymenants was one of the divers who took part in the dramatic rescue of a dozen boys and their soccer coach who got trapped in a cave in northern Thailand two years ago.

The Belgian has been researching possible locations for shipwrecks for many years, Horowitz said in an interview with The Associated Press, and Rivoire had a suitable boat to explore the leads he found.

Reymenants would ask fishermen if there were any odd spots where they’d lost nets, and then the team would use sonar to scan the sea floor for distinct shapes.

When they dived to look at one promising object, it was much bigger than expected, so they dug back into the archives to try to figure out which lost vessel it could be.

“And so we went back looking for clues, nameplate, but we couldn’t find any of those,” Horowitz recalled.

“And in the end, we took very precise measurements of the submarine and compared those with the naval records. And they’re exactly, as per the drawings, the exact same size. So we’re pretty confident that it is the USS Grenadier.”

The Navy command’s Underwater Archaeology Branch on average receives two to three such requests a year from searchers like the Grenadier divers, according to its head, Dr. Robert Neyland.

“A complete review, analysis, and documentation may take two months to a year to complete,” he said in an email to the AP, adding that it will likely take a few months in the case of this potential discovery.

The Grenadier left Pearl Harbor on Feb. 4, 1942, on its initial war patrol.

Its first five missions took it to Japanese home waters, the Formosa shipping lanes, the southwest Pacific, the South China Sea and the Japanese-occupied Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). It sank six ships and damaged two.

It sailed on March 20, 1943, from Fremantle, Australia, on its sixth patrol, to the Malacca Strait and north into the Andaman Sea.

The commanding officer, Lt. Cdr. John A. Fitzgerald, recorded what happened there in a report written after being freed from a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp in 1945.

On the night of April 20, the submarine glimpsed two small freighters and set course to intercept them the next morning, sailing on the surface for speed.

In the morning, a plane was sighted; an immediate crash dive was ordered, but the ship did not descend fast enough. Blasts from two bombs battered the sub; key parts of the vessel were mangled; power and lights were lost and a fire broke out. All hands desperately worked to fix what they could as Fitzgerald ordered the ship to stay on the sea floor.

When it surfaced after 13 hours it was clear the Grenadier was too crippled to flee or fight. An effort was made to rig makeshift sails on a periscope to reach shore before blowing up the vessel, but there was dead calm.

As dawn broke, two ships on the horizon were closing in. Codebooks and sensitive equipment were destroyed as preparations were made to scuttle the submarine. A Japanese plane made a run at the ship but was fought off with small arms, dropping a bomb harmlessly about 200 yards away.

The crew abandoned ship at 8:30 a.m. and an hour later were hauled aboard an armed merchant ship, which took them to Penang, a major port town on the Malayan Peninsula.

At a Catholic school requisitioned by the Japanese for use as a prison, events took an even darker turn.

“The rough treatment started the first afternoon, particularly with the [enlisted] men. They were forced to sit or stand in silence in an attention attitude,” Fitzgerald wrote.

“Any divergence resulted in a gun butt, kick, slug in the face or a bayonet prick. In the questioning room, persuasive measures, such as clubs, about the size of indoor ball bats, pencils between the fingers and pushing of the blade of a pen knife under the finger nails, trying to get us to talk about our submarine and the location of other submarines.”

After a few months, all the crew were transferred to camps in Japan, where the abuse continued. Four died from a lack of medical attention.

“This was an important ship during the war and it was very important to all the crew that served on her,” diver Horowitz said last week.

“When you read the book of the survivors, that was, you know, quite an ordeal they went through and to know where she finally lies and rests, I’m sure it’s very satisfying for them and their families to be able to have some closure.”

The Western Journal has reviewed this Associated Press story and may have altered it prior to publication to ensure that it meets our editorial standards.

Truth and Accuracy

We are committed to truth and accuracy in all of our journalism. Read our editorial standards.

Advertise with The Western Journal and reach millions of highly engaged readers, while supporting our work. Advertise Today.