Explorer's Sonar Image May Finally Help Solve Amelia Earhart Mystery - Everything You Need to Know

Aviator Amelia Earhart’s famous disappearance launched decades of speculation and fruitless searching. Now, businessman and ocean explorer Tony Romeo may have finally solved the 87-year-old mystery with the help of cutting-edge sonar technology.

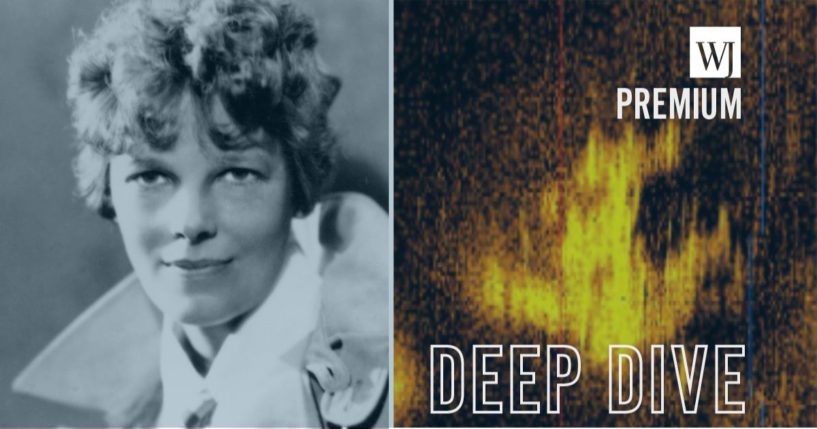

At the end of a recent months-long search for Earhart’s lost plane, a researcher aboard Romeo’s ship made a surprising discovery: Their sonar drone had captured an image resembling an aircraft 16,500 feet below the Pacific surface.

“In the end, we came out with an image of a target that we believe very strongly is Amelia’s aircraft,” Romeo said, according to The Associated Press.

View this post on Instagram

The Discovery

Romeo was a commercial real estate businessman before he founded the ocean exploration company Deep Sea Vision, according to The Post and Courier. He is also a former U.S. Air Force officer and a private pilot.

In September, Romeo’s 16-man crew set out to find Earhart’s Lockheed 10-E Electra, an object of popular fascination since Earhart’s ill-fated ’round-the-world flight in 1937.

They searched near Howland Island, a tiny atoll in the middle of the Pacific where Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, were supposed to have landed during the flight.

The team scoured more than 5,200 square miles of ocean floor around the island using the $9 million Hugin 6000, a submersible drone capable of scanning to depths of up to 6,000 meters (almost 20,000 feet).

View this post on Instagram

Romeo came close to giving up on the area.

“Day 89 or 90 comes, and we’re basically done, cleaning off the data for our next mission in American Samoa,” he told The Post and Courier.

It was then that one of the researchers realized that a seemingly corrupted sonar image captured two months prior wasn’t actually corrupted — and it looked an awful lot like a plane.

One hint that it could be Earhart’s plane was the shape of the tail, Romeo told NBC News.

“There’s no other known crashes in the area, and certainly not of that era and that kind of design with the tail that you see clearly in the image,” Romeo said.

“You’d be hard-pressed to convince me that it’s anything but an aircraft, for one, and two, that it’s not Amelia’s aircraft,” he added.

Earhart’s Family Speaks Out

Earhart’s great-nephew, Bram Kleppner, is hopeful about Romeo’s find.

“There have been many, many searches, and really not a single shred of evidence has ever turned up,” he told Fox News. “I would say we have learned not to expect anything from these searches.

“But … we feel like this is more likely than anything that’s come up. … The image they got does look like a plane, and it is in about the right place where Amelia would’ve crashed.”

Before the expedition, Romeo reached out to Kleppner’s mother, 92. Earhart, her aunt, disappeared just before her sixth birthday.

Kleppner’s family believes the most common theory about Earhart’s disappearance — that she and Noonan ran out of fuel and went down somewhere near Howland Island.

“They had to cross 2,500 miles of ocean. They’d been flying for a lot of hours. It’s a tiny island, and a miss in navigation by less than 2 degrees in either direction puts you more than 100 miles off land,” Kleppner said.

“That’s a pretty big area, and you’re searching at the bottom of very deep water looking for a pretty small plane. … All these people searched all these places, and no one has ever found a thing.”

Despite his optimism, Kleppner still has his doubts about the image captured by the sonar drone.

“It also kind of looks like an anchor. It kind of looks like a giant squid,” he said.

Earhart’s Disappearance

Seeking to become the first woman to fly around the world, Earhart took off with Noonan from Oakland, California, on June 1, 1937, according to Encyclopedia Britannica.

Nearly a month and 22,000 miles later, Earhart and Noonan reached Lae, Papua New Guinea, just north of Australia. They had 7,000 more miles to go before landing back in Oakland.

On July 2, they departed Lae for Howland Island, which sat 2,500 miles away, between Australia and Hawaii. A U.S. Coast Guard cutter waited near the island to guide Earhart’s landing.

But Earhart, dealing with overcast conditions, bad radio transmissions and low fuel, lost contact with the ship, according to History.com.

Earhart and Noonan never made it.

After an unprecedented search by the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard, the Navy’s official report stated that their aircraft likely ran out of fuel and crashed into the ocean.

View this post on Instagram

Earhart was officially declared dead in January 1939. But the search had just begun.

Since Earhart’s disappearance, ocean explorers have spent millions looking for the wreckage of her plane in vain.

Even Robert Ballard, who found the Titanic in 1985, came up empty-handed when he searched for the aircraft in 2019, according to The New York Times.

Theories

The famous disappearance launched a number of theories, too.

The most likely explanation seems to be the one mentioned above — that Earhart and Noonan simply ran out of fuel and crashed into the Pacific after failing to locate Howland Island.

But a more recent theory, addressed in a 2017 History Channel special, had to do with a photo discovered in the National Archives.

Some believed the photo captured Earhart and Noonan after their disappearance on Jaluit Atoll in the Marshall Islands, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

In the photo, Earhart supposedly sits on a wharf with her back to the camera while Noonan stands on the left. Even the aviators’ plane can apparently be seen on the far-right being towed on a barge.

The theory is that Earhart and Noonan were captured by the Japanese after their aircraft went down.

Found in a long-forgotten file in the National Archives, this photo shows a woman who resembles Earhart and a man who appears to be her navigator, Fred Noonan, on a dock. The discovery is featured in a History channel special, “Amelia Earhart: The Lost Evidence.” pic.twitter.com/3FxHq5lpP8

— Amelia Earhart (@aearhart1897) December 1, 2017

However, a Japanese blogger debunked that theory when he found the photo in a book published in 1935, two years before Earhart and Noonan disappeared.

Another theory is that Earhart landed on Gardner Island, where she and Noonan died as castaways.

British colonists found a partial human skeleton on the island in 1940, according to National Geographic. The island’s colonial administrator, Gerald Gallagher, believed it might have been Earhart’s.

The bones were sent to Fiji to be examined but were subsequently lost.

What’s Next?

Romeo plans on making another voyage this year.

He wants to confirm the image is Earhart’s plane, something he wasn’t able to do on last year’s trip because his drone’s camera was broken, according to The Post and Courier.

Romeo hopes to photograph the tail number of Earhart’s Electra: NR16020.

If it is the plane, he would like to raise it from the ocean floor and donate it to the Smithsonian, but that could be complicated for a number of reasons, according to the AP.

For one, removing the plane from its crash site could muddy one of aviation’s greatest mysteries even further.

“You preserve as much of the story as you can,” said Ole Varmer, a retired attorney with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and a senior fellow at The Ocean Foundation.

“It’s not just the wreck. It’s where it is and its context on the seabed. That is part of the story as to how and why it got there. When you salvage it, you’re destroying part of the site, which can provide information,” Varmer said.

Even if Romeo made a legal salvage claim, the plane’s owner could deny it, according to Varmer. The owner would probably be the Purdue Research Foundation at Purdue University.

In 1936, the foundation started the Amelia Earhart Fund for Aeronautical Research, raising $80,000 for the Electra, which became known as Earhart’s flying laboratory, according to Purdue’s website.

Earhart planned to return the aircraft to the school, according to the AP.

Perhaps the world is one step closer to knowing what happened to Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan.

“The mystery isn’t solved yet,” Romeo told The Post and Courier. “We still have to figure out what went wrong.”

Truth and Accuracy

We are committed to truth and accuracy in all of our journalism. Read our editorial standards.

Advertise with The Western Journal and reach millions of highly engaged readers, while supporting our work. Advertise Today.